Tri Bourne’s nurse was upstairs, in the living room of his three-bedroom house in Redondo Beach, Calif. In the vein of his arm was an IV, infusing thousands upon countless thousands of blood cells into his body. It’s a routine for him, once a month at least, to hook up that IV and have life shot straight into his bloodstream.

He talks with the nurse often. About life, yes, but also about myositis, the autoimmune disease that impacts only five out of every one million people in the country. She’s seen people who have been battling the disease for more than 20 years. There’s no known cure.

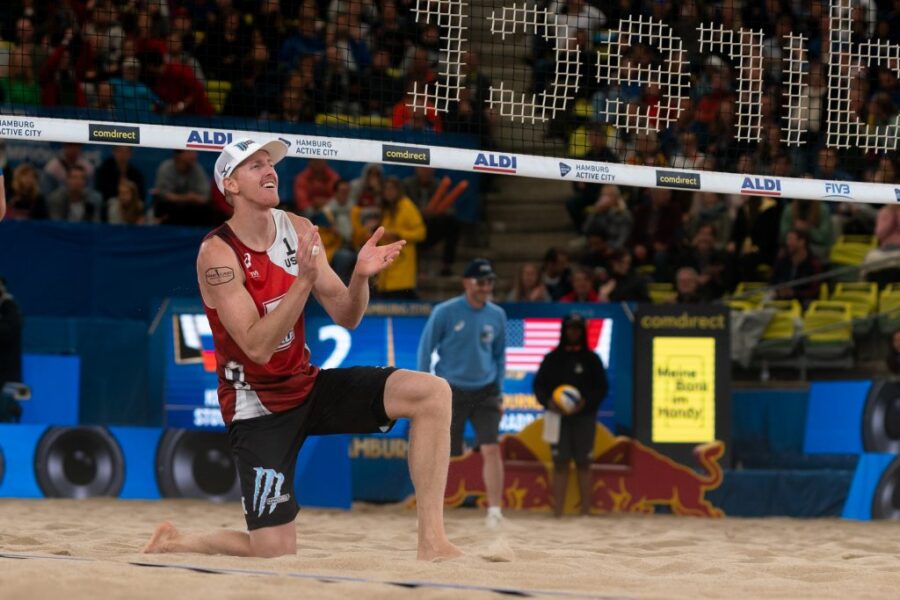

And yet to see Tri Bourne today is to see a man who is, while not cured — while potentially never rid of the disease that chronically inflames the very muscles that provide his livelihood — a personification of what the human spirit is capable of achieving when pushed beyond its usual limits.

On Sunday afternoon, in a parking lot in Long Beach, Calif., Bourne won an AVP tournament, his first in five years. He won against the longest of odds, a list of obstacles and potential for self-doubt long enough to cause most to retire or seek a new path. And, in a sense, when the autoimmune disease first struck and Bourne became so inflamed and swollen that competing was no longer an option, he did seek a new path.

He’s talked frequently on his podcast, SANDCAST: Beach volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter, about “leveling up.” In most cases, this is a reference to beach volleyball, and if you’d watched Bourne and Trevor Crabb any of the past three weeks during the AVP Champions Cup Series, you’d have no doubt he’s leveled up his game plenty. He’s learned to play defense, while maintaining his status as one of the best blockers in the world, despite standing just 6-foot-5. He’s able to withstand the pressure of receiving almost every serve, from two of the best defensive teams in the country.

But the court is just the court. He isn’t just on this Earth to win a few tournaments and disappear. Not that he ever was, but an unforeseen blessing of myositis was that it opened Bourne’s eyes to how ephemeral our physical abilities can be. One day, we can be finishing third at the 2016 World Tour Finals in Toronto. The next, we can be sitting in a hospital in Salt Lake City, with doctors probing his veins, running test after test, unsure what was happening to the body that very nearly competed in the 2016 Olympic Games.

So Bourne leveled up. He didn’t disappear during the 2017 season, the one in which he was not healthy enough to compete. He reinvented himself, commentating on the AVP’s livestream despite having little to no idea what he was doing.

Just pass the mic. I’ll figure it out.

Then he got his own mic.

It was his idea to start this podcast. We talked it over at the Ocean Diner, a wonderful little breakfast dive in Hermosa Beach that, no matter the time of day, smells of coffee and bacon. And in October of 2017, after he sat out of a beach volleyball season for the first time since he could compete with the groms on the Outrigger baby court on Oahu, we put out our first episode of SANDCAST.

The New Tri Bourne, we called it. Buddha Tri Bourne.

In a way, he was a new Tri Bourne.

He was a newlywed, married to the lovely Gabby Walsh, now Gabby Bourne. They had just returned from their honeymoon, in Bali. All his life, he had known the outdoors. Sports. Using his body to do things that most couldn’t, earning a scholarship to USC, then contracts in Puerto Rico, then a partnership with John Hyden and more prize money than he thought possible.

Just when he was supposed to be nearing his athletic prime, he wasn’t allowed to sweat. Instead, he was prescribed 45 minutes of meditation a day. He was 30 pounds lighter than usual, bouncing from one doctor to the next, experimenting with one treatment, then another. Maybe he’d return to the beach as a professional player. Maybe he wouldn’t. Nothing was certain.

“I had to have the conversation of ‘I might not play,’” Bourne said. “My nurse tells me about her other patients, and they’ve had this for 20 years and they’re still feeling the effects. They still feel the symptoms. I was like ‘Is that me? How long is this going to last?’ I had to have that conversation at one point, but I never bought into it. I was always like ‘Nah, there’s no way.’ You always have that positive outlook. It kinda depressed me to think about it like that. Three AVP [wins]? It’s significant, it’s multiple, it’s something to hang my hat on for sure, but I did that in my early 20s. I had my whole prime left. I want to creep up on the 20s so I’m on that list for a long time.”

His only certainty, then, was that there were some things he could control, and many he couldn’t. He simply focused on the ones he could.

He took up reading, something he readily admits does not come easy to him. He enrolled in acting, hosting, and improv classes with Gabby. He improved, quickly, weekly, as a host on this show. He watched film, seeing the game from a different perspective. He developed a wide-ranging skill-set he’s become quite fond of.

His body soon followed.

In early 2018, they found the treatment that worked best for his immune system. The inflammation steadily dropped, to the point that he could practice, lightly. He’d haul a bag of balls out to the beach, setting, hitting standing shots. He’d set balls into basketball hoops, hit against the wall. The touch, the feel, returned like an old friend.

He had played in, and won, tournaments prior to Sunday in Long Beach. He won his first tournament back, amazingly enough, in Qinzhou, China. But he and Crabb, while acknowledging it was a big win, a solid win — three-star FIVB gold medals are not exactly participation trophies — barely counted it. It was an AVP or a major, a fully loaded field, that he wanted.

It was what he got on the final weekend of the AVP Champions Cup, a weekend in which he had to beat the two teams — Jake Gibb and Taylor Crabb, Phil Dalhausser and Nick Lucena — who’d had his number.

Five straight times, they had lost to Gibb and Crabb. They’d dropped another three consecutive to Dalhausser and Lucena. It didn’t stop Trevor from inexplicably — even for Trevor, this was bold — guaranteeing a win, prior to the Porsche Cup.

It didn’t add any pressure to Bourne, in the finals. They’d already vanquished Gibb and Crabb in the quarterfinals. Dalhausser and Lucena awaited in the finals, where Bourne could get his first win since 2015.

He’d put an autoimmune disease at bay.

What’s an AVP final compared to that?

“Before the match I was thinking about it, during the national anthem, just reminiscing about it, and it was a crazy moment, thinking back to how far, how long that journey was,” he said. “It didn’t feel like there was that much pressure on it either. After how far I’ve gone, with all this stuff, I’m here. I’m just going to have fun with it. I’m going to go ball.”

He said this on his own show, with the silver Porsche Cup next to him, and an IV in his arm. He said this with his nurse upstairs, and his wife and newborn daughter, Naia, just steps away. It’s a different life than the one he likely envisioned to be living at 31.

A life in which Tri Bourne has leveled up.